On violence in street demonstrations, the nature of the Black Bloc’s actions

By Pablo Ortellado:

“”The democratic Estadão does not accept a reply for opinion articles, so I publish here my thoughts on the article by Demetrius Magnoli that appeared in yesterday’s edition of the newspaper. On violence in street demonstrations:

Last Thursday, Demetrio Magnoli published in São Paulo an article entitled “On the fringes of the Black Bloc” in which he criticizes a statement I gave to this same newspaper two weeks earlier trying to explain the nature of the Black Bloc’s actions. My statement sought to rescue the origin of the Black Bloc in the German social movement of the 1980s and its reinterpretation in the movement against economic globalization in the late 1990s.

In the statement I gave to journalist Bruno Paes Manso, I emphasized that the Black Bloc was born in the German social movement as a group dressed in black and dedicated to protecting street demonstrations from infiltration by agitators and the repressive attack of the police. In its second appearance, in the 1990s, the Black Bloc reappears as a predominantly symbolic tactic that should be understood more at the interface between politics and art than between politics and crime. This is because the destruction of property to which it is engaged does not seek to cause significant economic damage, but merely symbolically demonstrates dissatisfaction with the economic system or the political system.

There is obviously an illegality in the procedure of destroying a bank branch or a government building, but it is precisely the combination of risky civil disobedience and the inefficiency in causing economic damage to the company or government that gives this action its expressive or aesthetic meaning , in an expanded understanding. The destruction of property for no other purpose than to demonstrate discontent symbolizes and only symbolizes the abhorrence of economic exploitation or state domination.

This descriptive analysis of what I believe to be the nature and purpose of this type of action was considered by Magnoli to be irresponsible praise that would lead to the legitimization of violence as a fighting strategy. For him, explaining to a newspaper audience what the story is and what the purpose of a social movement’s action is is to make a dangerous apologia.

Magnoli draws a parallel between what I said and what some Italian social movement theorists who were wrongly accused of being responsible for the armed actions that took place in that country in the 1970s have said. In his analysis, he first connects the theoretical writings of the tradition autonomist to the armed struggle of groups from other political currents with which these texts have no relation; then, in a very anachronistic way, it suggests that just as some direct action movements of that period moved into armed struggle, the Black Bloc could also follow this path, despite the abyss separating these two historical moments.

As he had declared that he did not consider the Black Bloc’s strategy to be violent because its action was oriented towards things (bank branches or government buildings) and not towards people, Magnoli suggests that in Italy, too, armed attacks against people could be considered as directed towards things if these actions were seen as attacks on “symbols of the system”.

It must be said that this unreasonable inference that objectifies human life was not made by the Black Bloc who, unlike the police forces and commentators who legitimize repressive action, has shown to know the difference in value between a windowpane and the physical integrity of a human being.””

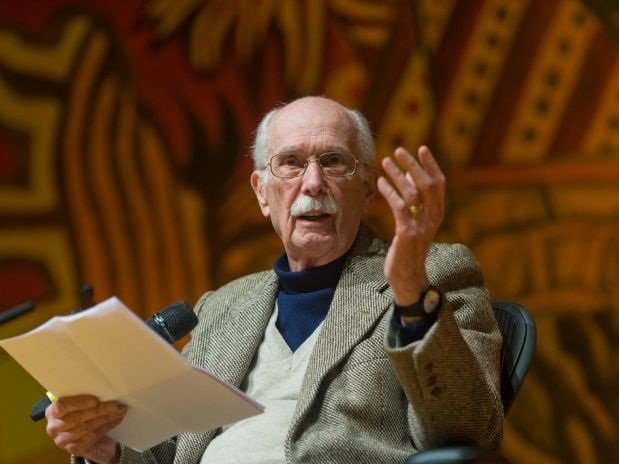

Pablo Ortellado take the opportunity to also rescue the text of Antonio Candido published in Folha on December 22, 1991 with the title “About Violence”:

“”In an article published on this page, the eminent professor Miguel Reale commented quite partially on the interview I gave, some time ago, to Jornal da USP. Highlighting an excerpt and separating it from the rest, he states that I raise the banner of violence and armed struggle, which is exaggerated and incorrect. Raising the flag means, if I’m not mistaken, enthusiastically proclaiming and advocating an idea or a type of conduct. This is not the case with my interview, whose keynote is different.

What I meant to say was that, for me, socialism has not ended and remains valid as a possible solution to the serious problems generated by economic and social inequality, and therefore to promote the humanization of man. Since the praise of capitalism as the only way is fashionable, I recalled that if it has become more humanly tolerable, it is not on its own merits, but because it has been forced to make concessions in the face of the struggle that socialism has been promoting for a century or so . I said more, that I conceive the position of the socialists according to a vision that I have called bifocal: in the distance is the ideal of an egalitarian society; close, the possible tasks in the society in which we live. By the way, I pointed out that, in my view, Social Democracy works well in the advanced countries; but in the Third World, like ours, I don’t see its viability, preferring to speak of democratic socialism.

What’s the difference? The Social Democrat (who outlaws the revolution) rejects the sharpest violence, while, in my view, the democratic socialist can accept it if it is necessary to achieve the ideal goals. Not because I like her, but because she is a kind of behavior that can eventually occur in political life. Finally, he said that, however, I do not think there are conditions in Brazil for the revolutionary path, and that the option is to act democratically in order to achieve what is possible. Therefore, the problem of violence was proposed at a doctrinal level and in a broad context, meaning something different from the simplification carried out by Professor Miguel Reale. In a word, it was not a question of advocating, but of recognizing its possibility.

But, as I may have ordered the ideas in a less clear way, I take the opportunity to quote another interview, to the magazine “Teoria & Debate”, in early 1988, whose text I was able to review. The interviewer asked: “Are you in favor of armed struggle?” I replied: “I prefer to pose the question in the following way: violence is not essential, it is a constant possibility and an eventual necessity of any political action, and that of the left is no exception. The problem is to know when and how it should be used, and that’s where the politician’s capacity is assessed. I am against romantic and individualist violence, against violence for the sake of violence. Often armed struggle belongs to one of these categories. But of course, when it is based on a correct revolutionary conception and is translated into the proper organization, it can be a decisive and necessary factor”.

By this I mean that I maintain my point of view, but in the context that I exposed it, including remembering the distinction between the plane of political philosophy and political practice. And I see now that it is inconvenient to put aside the concepts of revolutionary violence and armed struggle, because the recent history of Brazil has given this a very special connotation, with which I have never agreed, although I admire the capacity for sacrifice of many who in it they lost their lives, freedom and physical integrity.

That said, I cannot agree with Professor Miguel Reale when he says that Sorel would applaud my way of seeing. For me, violence is an instrument that may or may not be used; for Sorel, it is the inevitable path. Interestingly, he inspired the fascists on the right and the anarcho-syndicalists on the left. As I was neither one nor the other, I never adopted his point of view, which can lead to a kind of cult of violence. I say more: I have never advocated nor adhered to any of its forms in nearly half a century of participation in the socialist movement, and I see that, in Basil, it has been used in politics, in the absolute majority of times, by the right and the center, as it was in the case of the 1964 military coup, when impeccable liberals, lovers of democratic purity, law cultists encouraged it and adhered to it with enthusiasm. Professor Miguel Reale participated in it, as a member of the government of the State of São Paulo, and I remember hearing him on the radio, on the sinister night of March 31 (or was it April 1?), to communicate the outbreak and make an apology for the movement armed with a flame that, indeed, seemed to characterize those who raise flags.

Now, at that moment, was he convinced that he was practicing a democratic, legal and non-violent action? What he supported was an ongoing civil war, with General Kruel advancing along the via Dutra and General Mourão descending from Minas, with a bloody clash with the famous “military device” of which loyalist officials spoke. This did not happen because President Goulart, a peaceful and mild man, preferred to withdraw. He was the head of the nation, elected by popular vote, and coup supporters were subverting legality by force.

Note that I say this without the slightest intention of reproaching Professor Miguel Reale, who, at that time, acted in accordance with his convictions. My aim is to show with concrete examples that violence is an eventual ingredient in political action on the right, center or left. But when they use it, right and center tend to think it’s legitimate and beneficial, being intolerable and brutal when the left does it. To the right, it can even be “sacred”, as a very conservative intellectual wrote years ago on this same page, indignant because Governor Franco Montoro had not fired at the protesters who pulled down the walls of the Palácio dos Bandeirantes, in the early days of his mandate.

Also regarding the difference in assessment: Professor Miguel Reale is surprised because I say in the interview that, in the event of the eventual implantation of socialism, democratic coexistence should reign, with a multi-party system and a free press, with restrictions only for counter-revolutionaries, that is, , those who actively act in order to undo what has been conquered. The astonishment seems to me unjustified on the part of a participant in the 1964 armed movement, after which there was no shortage of jurists to say that justice should be more relaxed with its adversaries, since the so-called revolution created its own legality. And as for the plurality of parties, I remember that in 1965 they were all closed, including the Socialist, to which I belonged. It seems, therefore, that trampling the laws to facilitate repression and close associations is not violence if the initiative of the right. But, as Riobaldo says, “bread and bread is a matter of opinions”.””