Monet’s Falls

Monet was long-lived. He was born in 1840 and died in 1926, aged 86 years. In 1908, at the age of 68 and already a renowned painter, articles from the time documented the extreme dissatisfaction with his deteriorating vision, as well as the eruptions of anguish that led him to destroy his canvases. The reason: cataracts in both eyes.

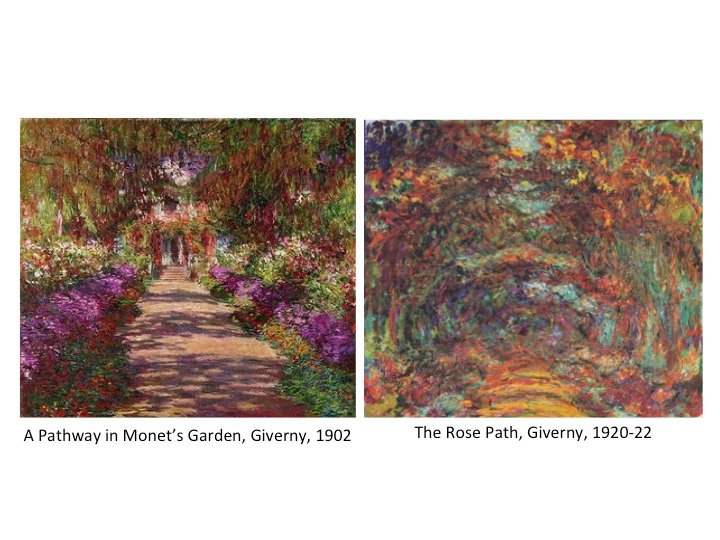

Cataracts are part of the natural aging process, when the lens is no longer transparent, becoming opaque and generating an increasingly blurry and yellowish vision (see paintings above: 1902 before cataract and 1920-22 already with advanced cataract) . In Monet’s case, this opacification may have been accelerated by the fact that he spent his life painting outdoors and therefore exposing himself more than usual to the ultraviolet rays that accelerate the lens’ aging process. In addition, Monet was a smoker, a risk factor for developing nuclear cataract, exactly the cataract he acquired. But cataracts already had a cure at that time: removal surgery with subsequent use of Mr. Magoo-type glasses to compensate for the absence of the lens that had been removed. Cataracts make it difficult for the blues to pass, generating a very yellowish view of the world and, after surgery, the world is no longer yellowish and becomes more bluish and little by little, the post-op adapts and the world goes back to the way it was before of cataract, neither too yellow nor too bluish. But it takes patience and much more patience in Monet’s days.

Very dependent on vision and color, very insecure and extremely anxious, Monet was very afraid of surgery. And to add to her fear, her friend Mary Cassat, also an artist, stopped painting after her cataract surgery. Despite his constant nightmares, he eventually surrendered to surgery when he became virtually blind and unable to work. Finally, at the age of 83 and after living approximately 15 years (1908-1923) with bilateral nuclear cataract that worsened over the years, the ophthalmologist Coutela performed in January 1923 two procedures (normal for that time) to remove his cataract (in the right eye).

Unfortunately the nightmares didn’t end after the surgery. Monet’s anxiety made his recovery very difficult. Along with this, the posterior part of the lens (which is not normally removed in surgery) quickly became opaque blocking Monet’s vision and in less than 6 months after the first procedure, he had to face a third surgical procedure that caused him yet. more anguish and suffering. Today, the posterior part is still not removed and when it becomes opaque it is not necessary another surgery but a laser application to remove the opacity. In Monet’s surgery, performed in his own home, an opening was made to remove this opaque part that prevented Monet from dedicating himself exclusively to adapting the new vision after the removal of the cataract.

Monet was not satisfied, he didn’t fit his glasses, and he was still extremely depressed. At that time, it took a lot of patience and time to regain his sight, but Monet was not only anxious, but he was old and worried about not having enough time to deliver his promised canvases to L’Orangerie. A year after the third procedure, Monet continued to say that it was better to be blind. Even dissatisfied, he tried to work on the Water Lilies series with Mr. Magoo glasses that had very thick lenses for the operated eye and very opaque lenses that blocked what little blurred vision he had left in his cataract eye, which had not yet been operated on ( the left eye, which was never operated on). At this time, Monet began to be visited by another ophthalmologist, Mawas. After a year of testing different colored lenses and two years after his last surgery, Monet eventually adapted and opted for glasses without colored filters.

In July 1925 Monet then felt that he had finally regained his true eyesight and worked vigorously to finish the ’19 panels he had promised’ to be installed in the future L’Orangerie that was being built especially for them. Monet delivered not only 19 panels but a total of 22, but unfortunately he died before being able to visit his installed work. It was his friend Clemenceau, who was always by his side, who closed his eyes as he left this world, but it was also Clemenceau who two months later helped the world to see better through Monet’s eyes with the opening of the Musee de L’Orangerie (Werner, 1998).

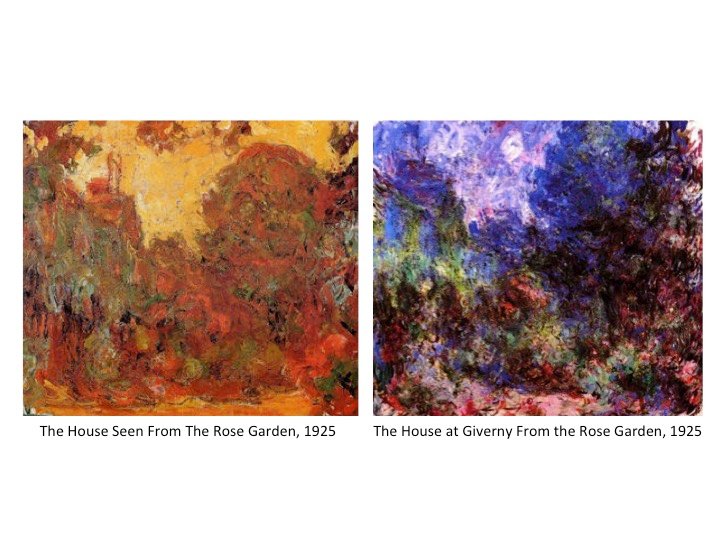

It is believed that the work on the left – quite yellowish – was performed before cataract surgery on the right eye or after surgery, but only with the left eye, which remained with cataract, and the work on the right was performed only with the eye right and after cataract removal surgery, generating a very bluish paint that contrasts with the yellowish world of cataract.

References:

Chapter Aging through the Eyes of Monet written by John S. Werner in the book Color Vision Perspectives from Different Disciplines (1998 ) Walter de Gruyter & Co., Berlin-NewYork.

Chapter Cataracts, Surgery, and Color: The Case of Monet in The Artist’s Eyes (2009) Abrams, New York, written by Michael F. Marmor and James G. Ravin .